On 6 June 1928, one hundred and fifty men gathered in London’s Goldsmiths Hall to celebrate the completion of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The guests were men who had served the Dictionary for decades or months or not at all. They ate Saumon bouilli with sauce Hollandaise, and they drank 1907 Chateau Margaux.

Among the guests was Professor J.R.R. Tolkien. He had not yet written The Hobbit, but after serving in WWI he spent a couple of years in the Scriptorium (a grand name for the garden shed where the Dictionary was being compiled) defining words beginning with Wa. We can thank him for waggle and walrus and warlock. I’d like to think he was also consulted on wizard, but there is no evidence of this.

Gentlemen representing The Times, The Daily Telegraph and The Manchester Guardian were also invited. As were scholars, editors, clerks, men of the cloth, knights of the realm and a humble school headmaster.

They poured into the Hall and found their places at three long tables arranged in front of another, higher, table. These were the lesser men, though some wore robes and most were in tuxedos. A bell rang and they turned to see the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, being chaperoned by the Prime Warden, Sir William Pope, to the high table. Other honoured guests followed and champagne glasses were filled with a 1917 Pommery & Greno.

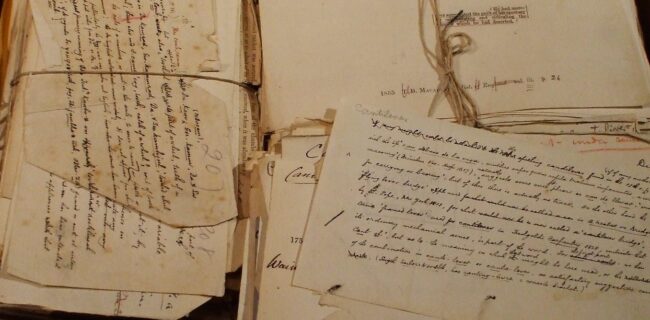

I know what they ate because I’ve seen the menu. I know who was there because I have a copy of the seating plan. I also know that there were three people who did not have a seat at any of the tables, but history records their presence in the balcony that overlooks the Hall.

I have had to imagine so much to make sense of why these three were missing from the guest list, and how it might have felt to watch the celebration unfold.

So here I am, on the balcony looking down.

It is a concession to the rules of Goldsmiths Hall that I am here at all, so I should be grateful. I look to my right, and there are the three: Edith Thompson, Eleanor Bradley and Rosfrith Murray. These women have been working on the OED for decades. Few men in the Hall below can claim longer service. Rosfrith is the daughter of Sir James Murray, the first and most celebrated editor. She has been employed to serve the Dictionary since she was 17. I follow her gaze to the high table where her brothers, Oswyn and Harold, sit opposite the Prime Minister. As children, they all helped sort slips containing quotations, but it is Rosfrith who chose to dedicate her life to the project. I look to Eleanor, her wire-framed spectacles make her look more serious than she is. Eleanor is the daughter of Henry Bradley, the Dictionary’s second editor. She has been collating and defining words longer than Rosfrith. And then there’s Edith, my favourite. She is an old woman now and I imagine she is reflecting on the first words she contributed to the Dictionary. Her name can be found among the acknowledgements of volumes from A to Z.

The soup course is served – tortue claire. Perhaps the Prime Minister has a distaste for turtle. He chooses now to make a toast to the editors and staff of the Oxford English Dictionary. He taps his silver dessert spoon on an empty crystal glass. The chime rings loud and clear. The Hall falls silent.

‘Perhaps before I begin I may make a confession about the Dictionary. I have not read it. But if ever a work was destined for eternity, that is it.’

Mr Baldwin speaks for some time. My companions and I lean on the banister of the little balcony, straining to hear. The movement is a relief; the seats are hard and the space cramped.

‘The Oxford English Dictionary is the greatest enterprise of its kind in history, and I ask you therefore to drink to the health of its editors and staff.’

The Prime Minister raises his glass and every man in the Hall does the same. It is a symphony of crystal and there is a jubilant congratulating hum directed towards those who are known to have spent their time defining the words. There are 150 men in that hall and not one looks to the balcony.

I turn to the women. Do they feel this snub as I do? I mime the raising of a glass. They are surprised to see me, but happy to play along. We come together in a silent celebration of the contributions they have made to this great enterprise.

I wish I could tell them that the Prime Minister was right, that the Dictionary was destined for eternity. And I wish I could tell them, that nearly a century later, the women who continue their work have been given a place at the table.