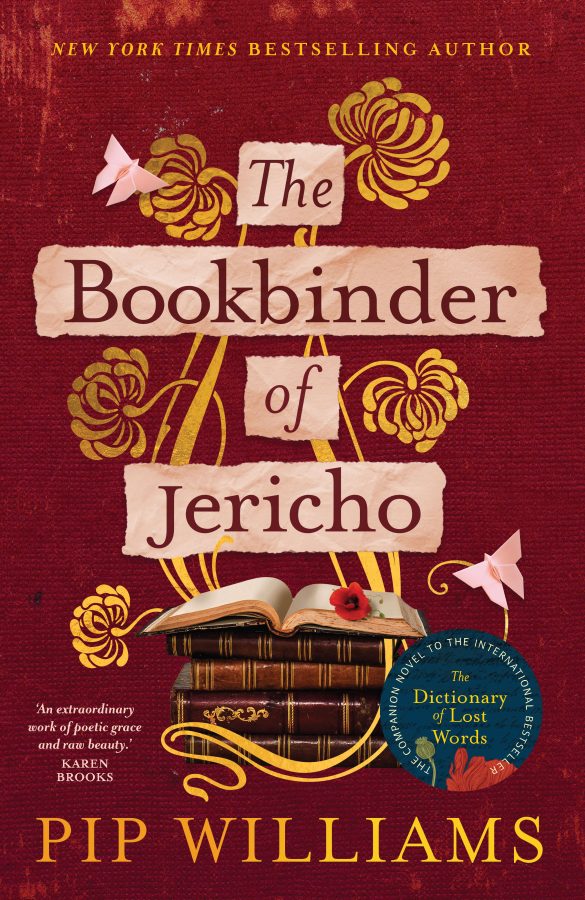

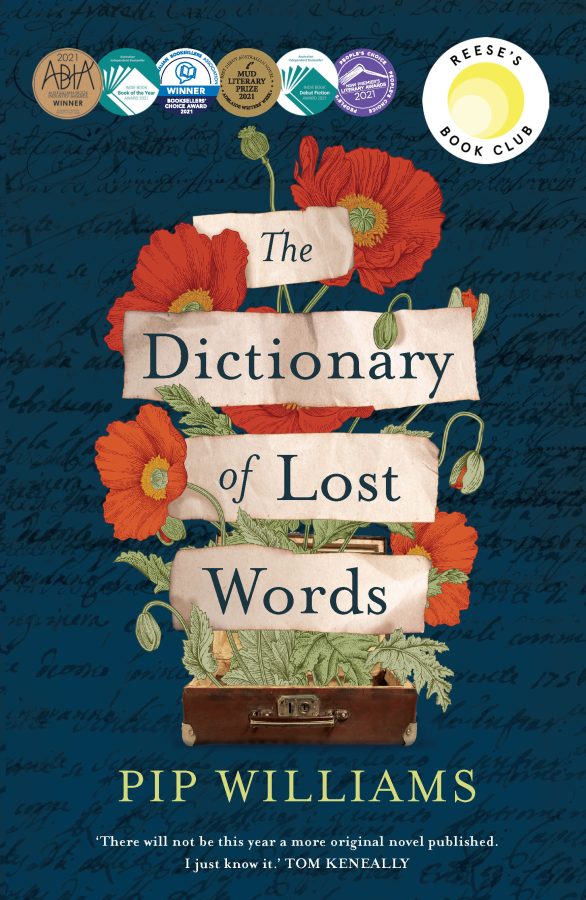

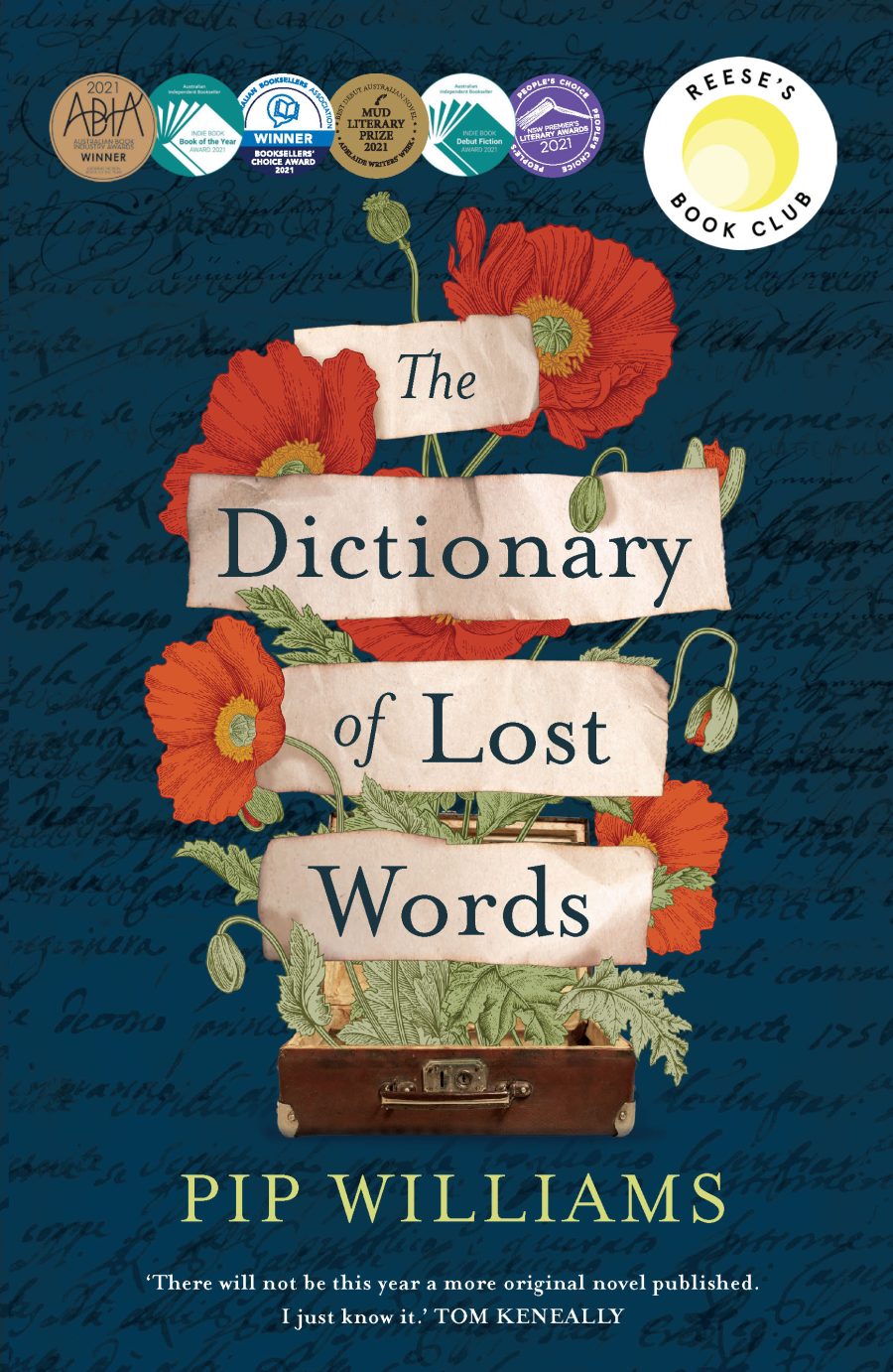

The follow-up and companion to one of the most successful Australian novels ever, The Dictionary of Lost Words

What is lost when knowledge is withheld?

In 1914, when the war draws the young men of Britain away to fight, it is the women who must keep the nation running. Two of those women are Peggy and Maude, twin sisters who work in the bindery at Oxford University Press in Jericho. Peggy is intelligent, ambitious and dreams of studying at Oxford University, but for most of her life she has been told her job is to bind the books, not read them. Maude, meanwhile, wants nothing more than what she has. She is extraordinary but vulnerable. Peggy needs to watch over her.

When refugees arrive from the devastated cities of Belgium, it sends ripples through the community and through the sisters’ lives. Peggy begins to see the possibility of another future where she can use her intellect and not just her hands, but as war and illness reshape her world, it is love, and the responsibility that comes with it, that threaten to hold her back.

In this beautiful companion to the international bestseller The Dictionary of Lost Words, Pip Williams explores another little-known slice of history seen through women’s eyes. Evocative, subversive and rich with unforgettable characters, The Bookbinder of Jericho is a story about knowledge – who gets to make it, who gets to access it, and what is lost when it is withheld.

What others are saying about The Bookbinder of Jericho:

‘Heart wrenching and bittersweet, The Bookbinder of Jericho is a lovingly woven story of hardship, longing and hope. Pip Williams writes with great insight and fascinating detail of working-class women, the war effort and World War I refugees. It was such a pleasure to spend time with these completely charming women.’ Mirandi Riwoe

‘I’ve longed to return to Williams’ distinctive blend of riveting historical detail and brilliant women. The Bookbinder of Jericho is everything I wanted and more.’ Toni Jordan

‘The Bookbinder of Jericho is an extraordinary work of poetic grace and raw beauty that will enfold readers in its powerful and moving narrative. A stunning companion to The Dictionary of Lost Words, this book is a classic and another triumph for Pip Williams.’ Karen Brooks

‘After finishing Pip’s beautiful book I had to wander along my shelves, taking my old books out and turning them over to see how they had been stitched together. The Bookbinder of Jericho will teach you things you’ll never forget – not just about how books were made, but who the women were who made them. Rich, deep and fascinating, it’s what all novels should be – a companion for life.’ Tegan Bennett-Daylight

‘Pip Williams has an unnerving and magnificent skill at creating characters who step off the page and directly into your heart and memory. In The Bookbinder of Jericho she asks her readers to pay attention to what has been overlooked – individual women and their labour, trauma and courage – and she does it with such style and grace. Reading Pip’s new novel felt like coming home.’ Kate Mildenhall

View my publisher’s book page: